- Home

- Michelle Knowlden

Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2)

Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2) Read online

Egrets, I’ve Had a Few

Deluded Detective Series

Book Two

A Novella

∞

Michelle Knowlden

Book Description

Pam Graff faces challenges after her last blackout. Ghosts in her bedroom, egrets on the stairs, and an obsession with climbing buildings are her new normal after suffering brain damage.

But no problem solving a cold case, right?

Once a physics teacher, she now works as a private investigator who sometimes moonlights as a fake fortuneteller. With the reluctant help of high school students, a genius hacker approaching his expiration date and her deaf neighbor, Pam battles lawyers, family, and rogues of the worst sort to discover whether a young hero-in-training is alive or dead.

While the dangerously handsome uncle might have been the reason Pam took the case, a series of odd coincidences force her to flee the FBI when she takes on danger of the killing kind.

Other books available by Michelle Knowlden

The Abishag Mystery Quartet

Sinking Ships: An Abishag’s First Mystery

Indelible Beats: An Abishag’s Second Mystery

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery

An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery

Deluded Detective Series

Jack Fell Down

Egrets, I’ve Had a Few

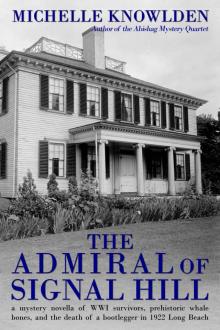

The Admiral of Signal Hill: a 1922 California mystery

Books by Michelle Dutton

Lillian in the Doorway: Orange Ranch Brides Book One

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Beginning

An excerpt from Sinking Ships: An Abishag’s First Mystery

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

Before the bough breaks

The branch swayed beneath me. The night air wafted cold against my cheek, and the tree creaked ominously. If a forty-something, high school physics teacher on disability plummeted to the earth, would it make front page of the Orange Country Register?

Would the obituary mention the coffee stain on my pajamas?

For Aunt Ivy’s sake, I did a swift calculation and swung to the rooftop of my two-story Anaheim townhouse. An upstairs light appeared next door and illuminated the oaks lining the sidewalk, which included the one I’d just abandoned. I crouched on the red tiles above the rain gutter. My feet and hands found easy purchase. When the light flashed off, I scrambled up the incline till I reached the top and perched there out-of-breath.

My aunt stood firmly against only one thing, which I think rare and admirable in a religious person. So many of them were against a mountain of issues, most of which I’ve found irresistible since my accident. A brain with wrecked impulse control did that.

Ivy was against unnecessary death. If I fell from a tree or slid off a rooftop in my pajamas, I’d surely strain her patience. She had waited by my hospital bed for the months I was either in a coma or slowly recovering. I shouldn’t put her through that again. With my lifestyle, I would undoubtedly die before her but no need to hurry the funeral. It had only been 20 months since that brush with death.

And yet I couldn’t bear another second in my stuffy, delusion-filled bedroom.

“Ms. Graff?” The thin whisper reached me from somewhere on the street below. It had an otherworldly quality, so I ignored it. Probably an auditory hallucination.

Since the old woman with the photograph appeared in my bedroom four nights earlier, I felt an urgent need for heights. I climbed a water tower in Placentia that morning. Over the next few days and throughout California’s North Orange County, I scaled hills, trees, walls, public buildings, and one elevator shaft. I now carried a ladder whenever I left home.

On the rooftop, I considered my investigation of the Tustin Tigers, a peewee baseball team, that may or may not have had something to do with my accident. So far I’d discovered no connections.

While I stared at the play of lights below me, I considered the cold case that came across my desk earlier this week about a missing seventeen-year-old. I generally only worked as a private investigator when I felt inclined. Teenagers went missing so often that even if I only tracked the ones on the police back burners and limited those to within a twenty-mile perimeter of my office, I’d still be too busy to eat, sleep or breathe.

This one interested me because the boy disappeared within days of the incident that killed my teaching career and a third of my brain. I woke in the hospital a mere block from his last known sighting.

“Ms. Graff?” The whisper was louder but too young to be my ghost in the bedroom. I heard a knock at the door below me. Since I didn’t entertain visitors at two in the morning, it had to be a delusion.

Nothing interested me about the teenager himself. I dealt with the species for decades, which kept me detached from them. He lost contact with most of his friends a year before he vanished. His parents reported him missing two weeks later, full of excuses why they hadn’t noticed him gone.

The man who’d called me yesterday had only become aware of his nephew’s absence when dropping off a birthday check for the boy’s youngest sister—a year and a half after the boy’s disappearance. If he hadn’t forgotten the birthday in time to mail the check, he may have continued his blissful ignorance months longer.

Hallucinations and other delusions were common with brain injuries of my sort, as were blackouts and the afore-mentioned impulse control issues. Phantasms appearing in ordinary locations were not unusual. Besides dogs and red-headed children that looked like Raggedy Anne dolls, I’ve seen egrets in my kitchen, Maria Callas singing a Puccini aria at the Farmers market, and Captain Kirk racing towards a burning courthouse. A hazy woman holding a photograph would normally not be noteworthy.

The knocking below suddenly cut off. I heard the phone ring in my condo. My delusions were persistent tonight.

Since my blackout almost 90 days ago, I’d been loathe to mention the ghost woman to my neurologist, psychiatrist, or Aunt Ivy. I’d never told them about the egrets, opera singers, or Captain Kirk. Medical personnel and relatives became overly concerned about hallucinations, too eager to advise medications and measures that I had no intention of taking or doing. I’d been looking forward to driving again. Only another blackout in the next few days would stop me.

Should I take the case or not? Normally I’d focus on the ghost in my bedroom, but I didn’t know where to begin. It’d be easier to pin down the egrets.

I could go no further with the Tustin Tigers. Unfortunately, my only distraction appeared to be the missing boy.

The top of a ladder appeared suddenly before me and leaned against the roof. Fascinated with this new development, I watched it quiver till a head of silky black hair appeared.

“Ms Graff.” The voice, filled with reproach and angst, could belong only to one person.

“Kirsten?”

“Who else would it be?” she demanded. “What are you doing up here when you’re supposed to be answering your door?”

“Why are you standing on a ladder at my house at two a.m.?” I countered.

She huffed with exasperation in the dramatic way only sixteen-year-old girls could do well. “Because you told me to.”

I blinked at her. Was she delusional also? Then the light dawned.

“Two in the afternoon, Kirsten. I needed you to drive me somewhere tomorrow—or that would be today, at two p.m.”

She glowered. “You said two. This is the first two since we talked.”

One cannot tell a teenager that two in the morning is not a logical hour to meet. Adolescents infer the most bizarre meanings fro

m an ordinary request, which I should have remembered. I was out of practice.

If I could have traded up to an honor student or at least to something more sensible than a sixteen-year-old majoring in fashion and football players, I would have done so in an instant. Unfortunately, she and her linebacker ex-boyfriend needed community service credits, and I needed drivers and reality-checkers.

“So since I’m here anyway…” she said.

No problem. I could adapt my mission to the early hour. I slid down the roof, which made considerably less racket than Kirsten did with the knocking and the talking. Still my quiet coast down the tiles activated my neighbor’s light again.

Since I had to change, I re-entered my house via the tree and my bedroom window. Kirsten groused, descended the ladder, and stowed it behind the bushes where I’d kept it lately. I thought about asking her to bring it with us in case an urgent need to climb assailed me, but figured we wouldn’t be able to fit it in her car.

The woman holding the baby’s photograph still stood in my bedroom, still weeping. Delusion or not, I couldn’t bring myself to change clothes in front of her. Since the egrets had moved into the bathroom while I was on the roof, I’d dress in the hallway. I grabbed the first thing I found, the getup I wore while playing Madame Pythagoras—the fake fortuneteller who guides misguided youth to the straight and narrow. Last time I’d used it was on Kirsten, and we see how well that went.

I threw on the light shawl, slipped into embroidered slippers, wound a scarf into a turban around my head, and added a half dozen gypsy bangles to my wrist. Good to go.

Kirsten’s eyes widened when I opened the door. “I’m not going anywhere with you looking like that.”

She was dressed like an exotic dancer with enough makeup for a kabuki theater production. I ignored her and headed for her mini Cooper.

“Where are we going?” She gunned the engine with only a hint of sulking in her pursed lips.

“My office,” I said. “Then I need to hit the Imaging Center.”

“Good. I been meaning to talk to you about your image.”

“Funny. Wrong kind of image.”

We stopped at a 24-hour coffee shop and picked up lattes and muffins to go. The baker worked early hours. My pumpkin muffin steamed gently when I tore it open.

I reminded her to lock her door after we parked outside my office building. We weren’t in the nicest part of Santa Ana during the safest time of night.

I opened the case file the uncle left while Kirsten strolled around my office.

“Remember when you acted like a gypsy and told us all that psychic stuff about me and Devlin to break us up?”

I didn’t respond because I’d already lost her attention. The reminder of her ex-boyfriend triggered Kirsten to text him.

I often took jobs from parents willing to take extreme measures with children they could no longer control. I would like to say that I’d only done so since the accident, but my side career as a fortuneteller started years earlier. The plus side of brain damage meant that I no longer needed to rationalize my methods. Madame Pythagoras happily exacted mild trauma on youths.

“He’s cute.” She leaned over my shoulder to stare at the missing boy’s case file picture. Tyler Hinshaw. Her latte dribbled down the back of my shawl. “Is that who we’re gonna save?”

CHAPTER TWO

After the break-in

“I didn’t think teachers, even Physical Education teachers with brain damage, burgled hospitals.”

Although she’d repeated this four times, I corrected her again. “This is an imaging facility, not a hospital. I was a Physics teacher, not PE.”

“Whatever.” She waved a few fingertips painted so fluorescent that I saw light trails in the gloom. “Am I like an accessory?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Exactly like an accessory.”

A few months ago, I noticed that the place where I went for MRIs had the same security system that Dante had taught me to circumvent. A skill that came in handy now. It took less than three minutes to disable the alarm and open the front door.

The center’s part-time accountant, a former LA County prosecutor, used her office at the Imaging Center for her legal clients. They couldn’t afford her rates, but she rarely charged the impoverished ones for consults.

“You hacking into that computer?” Kirsten asked.

“Hacking isn’t the right word.” I missed my latte that I’d left in the lobby. Working at Bobbi’s desk, I didn’t dare leave a skin cell behind, much less a hint of vanilla. Bobbi would know.

A casual conversation while I waited for an MRI a year ago cemented my relationship with the former prosecutor and made Bobbi a handy contact when I needed information. I’d called her yesterday and she promised to have a file ready on the kid when I arrived for our 2 p.m. appointment. Kirsten’s early arrival and my impulse control issues meant I could harvest the data twelve hours early.

Someone should invent a new term for the elegant way Dante had trained me to break through firewalls and thwart robust security systems. Hacking sounded too crude. In minutes, I mined Bobbi’s files and decrypted backdoor links to her former employer.

While family and witness interviews printed, I realized I’d lost Kirsten. A nerve pinged.

I located her in the records room. Seated at a desk, she moodily flipped through a patient record while eating her muffin one crumb at a time.

“Don’t get grease stains on that.” Belatedly I added, “And don’t read it. Patient information is confidential.”

“Really, Ms. Graff? I wouldn’t have known that ‘cept for CONFIDENTIAL being stamped in gargantuan letters on the cover.”

Impressed that she knew the word “gargantuan” and used it correctly in a sentence, I said, “Put it back where you found it, and let’s go.”

She carefully put another muffin crumb on her tongue and savored it. “You should see this, Ms. Graff. This kid’s my age, but it’s okay if I know his private deal since we go to different schools and I won’t ever meet him. He’s got one of those unpronounceable tumor things. I so feel for him.”

My eyes suddenly misted. Could I be seeing one of those rarer than a millennial event—a teenager exhibiting an empathetic moment? I cleared my throat, but Kirsten spoke first.

“Can you imagine living in those hospital gowns and paper shoes for days and days? It’d be a total nightmare.”

We suddenly returned to the real world. “Uh huh,” I said. “Clean up. I’m ready to go.”

Even though I erased our appearance on all the security videos, sent a text cancelling our 2 p.m. meeting and made sure we carried out our trash, I suspected Bobbi would call me minutes after she arrived. I pushed Kirsten through the front door and wiped down the handles.

Dawn crested the mountains behind us as Kirsten dropped me off at my townhouse. I felt a rare affection for her as the small red car zipped out of sight. I might have wondered if either my hardened teacher-self or brain-damaged emotional centers had transformed to something cuddlier—except that I generally liked her best as she waved goodbye.

I packed a thermos of Keurig breakfast blend coffee and the pilfered interviews into a backpack and headed for the roof. I threw in an orange from the gift basket on the table.

Eight months ago, I’d turned down a case because it was too easy. After looking over the police record and talking to the parents, it seemed obvious to me that the nineteen-year-old was either at her grandparents’ cabin in Big Bear or at her girlfriend’s apartment in San Diego. If the parents had told the cops the circumstances behind their rift, the police would have solved the case months ago. The idea of stringing the family along while large investigation bills mounted bored me, so I told them I wouldn’t take the case. I did tell them where she could be found. Like a bad dream, the fruit baskets appeared a week later and every month since.

My neighbor’s light briefly flashed on and off as I crossed the red tiles. I only had an hour before the world headed for Starbu

cks and traffic jams, but that was time enough to learn about the day Tyler Hinshaw disappeared.

After I’d drained half the thermos and heard the first garage door on my block rise, I returned everything to the backpack. I slid down the roof and stepped from tree to bedroom window. The older lady with the photograph had vanished as expected. She appeared only at night, which was strange for two reasons. One: she glowed as if lit by the sun. Two: daylight did not similarly hobble the egrets. After taking a shower and dressing, I walked through one on the stairs.

I checked phone messages. Predictably one was Bobbi fuming about the break-in. Tempted to call back and ask what clue I’d let slip in my covert operation, I decided to wait a few days instead. An instructive critique of my spy skills could wait till she cooled.

In the next message, my aunt cancelled our dinner because of a death in her congregation. Great. It was the only event on my calendar for the next three days.

I could fill the time with Tyler’s case. Still, even after the morning’s efforts, I remained dead set against it for all the aforementioned reasons of cold case difficulties. And because I just didn’t feel like it.

Inertia, one of the strongest forces in the universe, weighed on me. I reflected on other forces in the universe, and then I opened my tablet. Using a facial reconstruction app Dante appropriated from Homeland Security, I’d created a fair representation of the woman in my bedroom the first time she appeared. Using another app to correlate the jpeg to photos on various websites, I checked daily for matches. Still none. I widened the sites to social media.

Since that might take a century to sift, I switched to another unproductive activity. In my pre-brain damaged days, I knew when to surrender. Unless it involved missing teenagers, my damaged brain now didn’t know when to stop.

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2)

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2) Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1)

Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1) Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries)

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries) Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2)

Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2) An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4)

An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4) Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1)

Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1) The Admiral of Signal Hill

The Admiral of Signal Hill