- Home

- Michelle Knowlden

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries)

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries) Read online

Riddle in Bones

An Abishag’s Third Mystery

∞

Michelle Knowlden

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery

Copyright 2014 Michelle Knowlden

Kindle Edition

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of various products referenced in this work of fiction, which have been used without permission. The publication/use of these trademarks is not authorized, associated with, or sponsored by the trademark owners.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you are reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to Amazon.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the author's work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My heartfelt thanks go to:

My Beta Readers: Kris Klopfenstein and Jeanine Gattas

OC Fictionaires: for support over too many years to mention and especially for the encouragement and comments for this novella.

Cover Artist: Bethany Barnette ([email protected])

Just because: Linda, Jean, Becky, Ken and Debra

DEDICATION

To my family with love

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Bainbridge Dictionary definition of Abishag

An Excerpt from An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery

About the Author

Bainbridge Dictionary, Seventeenth Edition, published November 2012,

Abishag (also Abishag the Shunammite)

last wife of King David, mentioned five times in 1 Kings

from 1 Kings 1-3: Now King David was old and advanced in years. And although they covered him with clothes, he could not get warm. Therefore his servants said to him, “Let a young woman be sought for my lord the king, and let her wait on the king and be in his service. Let her lie in your arms, that my lord the king may be warm.” So they sought for a beautiful young woman throughout all the territory of Israel, and found Abishag the Shunammite, and brought her to the king. The young woman was very beautiful, and she was of service to the king and attended to him, but the king knew her not.

Abishag (also Abishag wife, bed-warmer wife)

In 1997, the state of Arizona legalized the practice of providing Abishag wives for comatose men that adhered to strict guidelines, contracts for the patient, patient’s family and service provider, and scale of payment for said services.

In 2002 the US Congress, recognizing the need to standardize the practice of using Abishag wives as part of hospice care, limited providers to certified agencies and Abishag wives to licensed personnel. While an Abishag wife signs a marriage certificate with the patient’s power of attorney, it is the agency contract that defines her role, income during the patient’s last days, and severance pay upon the patient’s death. The terms of the contract have been updated by the Supreme court thirty-eight times between 2002 and 2011.

In 2004, after the landmark case of Shulman v Miami Abishag Agency where it was argued that the emotional maturity required for Abishag services exceeded the current legal definition of adulthood, age restrictions were established: no females under the age of 18 shall be licensed as Abishag wives, and females between the ages of 18 and 21 are required to provide a parent’s signed consent for each contract.

CHAPTER ONE

Jen asked me later if I had seen portents that day, but nothing seemed out of the ordinary in Palm Desert’s Institute of Desert Antiquities laboratory, nothing hinted at trouble looming. As a student of mathematics, I don’t believe in premonitions, although as a romantic rationalist, I wished I could. I think the future should be murky, as if veiled in the mists of Avalon.

In a hallway that smelled of acetone, cactus and graves, I tried calling Donovan. My finger hovered over his name as I remembered how he broke up with me when he found out I married another comatose man. That was eight months ago. He still worked at the Abishag agency as principal counsel—Jen kept me informed.

“Miss Greene? I need those mule bones now.”

I pocketed the phone and picked up the long, wide box of bones. Still thinking about ways to get Donovan to call me back, I slid the box onto a lab table, scattering a raft of notes.

Hunched over the lab counter, Doctor Henry Telemann keenly studied a desiccated harness as if he held Cleopatra’s headdress. I rattled the box, but he’d already forgotten the bones and me.

If you measured the magnitude of peccadilloes, then Jen at six dead husbands far exceeded my measly two. I tried that defense when Donovan confronted me in the La Jolla home of my dying second husband. He informed me icily that Jen wasn’t his girlfriend, I was.

Smoothing his cropped red hair, his blue eyes narrowed. “I should say ex-girl friend.” Before I could plead for forgiveness, he disappeared in a black whirl of his Italian business suit and musky cologne.

“Are you seeing this, Miss Greene?” Doctor Telemann tapped vertebrae back in place. I blinked. Lost in thought about how to get Donovan interested in me again, I’d somehow missed the anthropologist opening the mule bone box and laying out the contents.

“Seeing what, sir?” Like everything else in my life, I missed the big picture.

My housemates, Kat and Dog, assured me that Donovan had never been right for me and I would find someone better. Although Kat was my age and Dog only three years older, the other six housemates called them Momma Kat and Dog Daddy for their tendency to parent us whether we needed it or not. Although Kat and Dog had been against me signing those two Abishag contracts, they’d been there to help me both times, even risking their lives to do so.

I envied their love for each other that spilled over everyone around them. That kind of love would never be mine. Jen had warned me that ex-Abishag wives didn’t get boyfriends. Once a…the rude term is bed-warmer for a comatose man, guys treated you differently. Like you smelled of embalming fluid.

I’d been lucky that someone like Donovan Reid—a successful, good-looking, young attorney—called me. I know because he told me so often. His tolerance stopped with my second husband Jordan, and I would never find anyone else.

Hence the urgency to rekindle his interest.

I fiddled with the hipbone—it looked skewed to me. “Stop that,” Doc T said with irritation, and then he tilted his head. “No, wait, Miss Greene. You got it. Something’s wrong with that hip bone.”

I’d been lucky to land a job this summer. I married my first comatose husband Thomas a year ago because after a dozen short-lived jobs, I had been branded unemployable. I found it difficult to deal with people. I once worked as a waitress in a coffee shop, the most efficient server they’d ever had. After three days, they let me go because of a tendency to “brow-beat customers into ordering faster.”

“Ante-version. Now why would a mule’s hipbone be twisted inward like that?”

/> “Don’ know,” I said tiredly. It had been eleven straight days of studying dusty, dirty bits and drabs from a six year old dig in Palm Springs, trying to fill in some holes, literally, in California desert life a hundred years ago.

He picked up the harness again, and I yawned.

The Abishag stipend with a bonus from my second husband’s estate had generously filled my savings account. It would be a long time before I needed more funds. If I never dated again (and the chances of never dating again looked excellent), then I could stretch my current finances till graduation in two years. Dating Donovan required a wardrobe of haute couture that crippled me financially, the reason I had married the nearly-dead artist Jordan Ippel.

Sebastian Crowder, grandson of my first nearly-dead husband, found this summer job for me with Henry Telemann. Like the distractions of school, working in the lab went a long way to stop me from fretting over Donovan but didn’t halt my scheming to get him back. Dog and Kat approved of the job, partly because they thought Palm Desert a safe distance from Donovan and partly because Kat decided Sebastian wanted to ask me out.

Nice thought, but he did not. True, dangerous art forgers and killers showed up at Jordan’s house, and he hadn’t deserted us. Despite what Kat believed that did not mean that Sebastian liked me in that way. He stayed because of loyalty to Jordan. Though we were both in college—me in my third year, him starting his doctorate—and he lived in Santa Monica close to UCLA, did he call me after his grandfather’s death? Okay, so I was dating Donovan at the time, but still he never called.

Did he call after Jordan Ippel died, after the police finished their investigation and made their arrest? He did not. Not once during the winter quarter, not a peep during the spring.

I thought since Sebastian found this job for me and had been working for Doc T for a year, I would see him more often this summer. Didn’t happen. I knew he hadn’t returned to Santa Monica, but I’d not seen him since we drove here from LA in his beater car.

He and the professor had been working in the Palm Desert museum, which housed the artifacts, and in the Institute of Desert Antiquities since late May. I had to re-take Sociology 101 during the summer session, so I didn’t join them till August. I failed the class the first time. Even with Kat tutoring me, failing again seemed inevitable. Understanding human social interactions will always be a mystery to me.

“You’re standing in my light, Miss Greene.”

Doctor Telemann said that to me a lot. He also sighed when I broke something or asked a stupid question or fell asleep reading old mining journals. In the beginning, he sighed so much that I thought him asthmatic till I figured out I was getting on his nerves again.

I liked the old coot but figured he’d fire me at any moment. When I accidently torched a dozen 103-year-old blacksmith receipts, I was astounded he hadn’t fired me on the spot.

One night while working late over what he thought might be a Native American saddle blanket, he brought up the subject of Abishag wives. He asked with such vague curiosity, such guilelessness, that I found myself talking about my sophomore year financial crisis, my parents’ approval, and how they later leveraged my new connections with wealthy tycoons and famous artists for my father’s political aspirations. I also mentioned the murders that happened with both marriages.

“Murders?” Doctor Telemann absently squeezed a stack of desert land deeds from the early 1900s and paper flaked onto the table. I gently wrested the deeds from him.

“Murders,” I said firmly. “Marriage to the wealthy is not the cakewalk you’d think. But ask me no details. An Abishag wife is always discrete.”

He looked wistful but didn’t ask again about the murders. Instead he used those long hours of brushing bones, sorting land deeds, and lining up mule vertebrae to ask about Abishag marriages.

It’s not that I haven’t been asked before, but I knew when someone only wanted the sordid details. By the way, there aren’t any. Trust me. Doctor Telemann wasn’t like that. He was more interested in the differences between a traditional marriage and an Abishag contract than in what exactly were the parameters of therapeutic touch. Really, people can be so stupid.

But not Doctor Telemann. I suspected Doctor Telemann didn’t know about any sort of marriage. A kind of innocence softened his face as he asked his questions. Although the sum of my two marriages didn’t add up to 25 days, I had more experience than he did.

I explained my own theory of love, which fell under what I called romantic rationalism. “As a romantic, I believe in love and Prince Charming, in glass slippers, dragons, and gingerbread cottages. As a rationalist, I don’t believe in happily ever after. Nothing lasts: not the love or the charming or the glass slippers. Only axes and poisoned apples.”

Doctor Telemann looked distressed. “I don’t think I’m a romantic rationalist, just an old bachelor who gave up on marriage a long time ago.” Later, when I spilled coffee on the mule’s jawbone, he told me that he’d been in love once, but she’d belonged to another. He’d never found anyone else who suited him like she had.

He smiled wistfully: “She was my Guinevere.”

I squinted at Doc T, but I could not imagine, even in his far away youth, that he’d been that master of medieval jousting, Lancelot.

I considered telling him about compromise and Donovan Reid, but I couldn’t corrupt that sweet innocence. Better that he’d loved once, really been in love, than test the dodgy waters of dating.

On this eleventh evening of my desert job, I took pictures of the mule’s twisted hipbone to send to a veterinarian Sebastian knew. Yes, Sebastian finally appeared in the lab as Doc T and I finished for the day. His shock of black hair unruly as usual, his eyes appeared shadowed with fatigue. Obviously seething about something, he curtly gave me the vet’s number, answered Doc T in monosyllables, and didn’t look at me even once.

Doc T handed Sebastian a shoebox that rattled like bones and believe me I now recognized that sound. “Take this back to Claremont with you,” he said. “Put it in my university office when you get a chance.”

Sebastian took the box and stomped out of the lab.

I didn’t know he was going back to LA. “Am I staying here with you or going with Sebastian?” I asked. Since he had the only car, I figured Sebastian would have to take me home when Doc fired me.

“You’re staying. The boy’s got some business at home. Said he’d return tomorrow.”

“You’re not firing me?”

He stared at me in surprise. “Fire you? Why would I fire you? You’ve lasted longer than any intern I’ve had here. It’s 120 degrees in the shade, most of the town has flown north, and we’re doing the dullest work imaginable in physical anthropology. If I had the funds, I would give you a raise.”

I laughed. I really did like him. Sebastian told me more students attended his seminars than any other on campus. Back when Sebastian still spoke to me.

“An old friend’s dropping by the lab and taking me to Sherman’s for dinner,” Doc T said. “You should get a ride back to the motel with Sebastian.”

I grabbed my purse and headed for the door, expecting Doc T’s last question, the one he always asked as I left for the day.

“Miss Greene?”

I grinned, my hand on the doorknob, and turned. “Yes, Doctor Telemann?”

With that familiar wistful smile and his head slanting left, he asked, “If I were a wealthy comatose man, do you think an Abishag wife would choose me?”

I said the same thing, I always did. “Doctor Telemann, if I were still an Abishag wife, I’d like no one better.”

With a happy nod, he wished me “Good night.”

It was the last thing he would say to me.

CHAPTER TWO

I ran to the parking lot, the wall of heat making me gasp. Doctor Telemann’s shoebox of bones still tucked under his arm, Sebastian paced around the car, listening to his cell phone, his eyebrows knitted in a frown. When he saw me, his frown deepened.

Curtly, he rang off and scowled. Undaunted, after all when I had been married to dear nearly-dead Thomas Crowder, I’d been Sebastian’s step-grandmother, I said, “Doctor Telemann is meeting a friend for dinner. Would you drop me off at the motel?”

Acting like it was a huge inconvenience when we both knew he would be picking up the freeway near the motel anyway, he nodded and opened the trunk to stow the shoebox.

As I opened the passenger door, we both jumped, hearing what sounded like a gunshot. “Where…” I began, but Sebastian ran for the Institute’s back door, the same one I’d just exited.

We raced to the stairs and down two flights to the lab. The door was open. I remembered closing it as I left.

I smelled gunshot residue. Feeling faint, I stalled at the doorway. A year ago, Annette Reich held a gun on Kat and me in Thomas’s Palos Verdes home. I would never forget the sound and smell when she fired, narrowly missing Kat.

Sebastian shoved past me, mule bones crunching under his shoes. “Henry,” he shouted, dropping to his knees behind a counter. “Les, call an ambulance.”

No signal, so I ran back up the stairs, not stopping till I reached the entrance. I shook the glass doors. Locked. A small pickup truck skidded from the front parking lot.

I called 911.

Seconds later, I ran back to the lab trying to figure out how the shooter had left the building without passing us on the stairs. Had it been someone associated with the Institute? Someone with a key and access to the exits?

I knelt behind Sebastian, who held a bloodstained rag to Doctor Telemann’s head. “Is he breathing?”

He nodded. “I stopped the bleeding, looks like a through and through. In Paraguay, I saw a guy with a welding rod driven through his head. He turned out okay. Brain totally repaired itself.”

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2)

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2) Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1)

Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1) Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries)

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries) Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2)

Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2) An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4)

An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4) Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1)

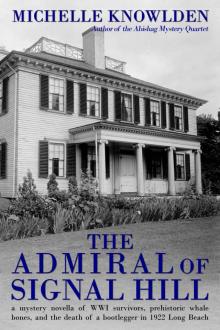

Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1) The Admiral of Signal Hill

The Admiral of Signal Hill