- Home

- Michelle Knowlden

Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1) Page 2

Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1) Read online

Page 2

When I taught high school, I separated students into two buckets: Murdered Before 30 and Not. Bullies, victims, and weak-brained followers went into the first bucket. Only sociologists and unemployed criminologists tracked these statistics, but Aunt Ivy liked reading the week’s obits aloud over Saturday morning breakfast and had since I was thirteen. Through twenty plus years teaching, I tallied my dead students while eating toasted bagels topped with Nutella and found my prognostications eerily accurate.

So with reasonable credibility, I assessed the female as recovering from a brain tumor—not a gunshot—and turned my attention to the other patient. While flipping through his magazine, he would pause, hand frozen in mid-air, eyes glazed. Easy diagnosis. An epileptic whose petit mal seizures indicted that his medication needed tweaking. Although he was half my age, I’d consider dating him. Serious eye candy, he looked like an actor on one of those Latin soap operas.

I had a purpose for studying my fellow patients. Although I could afford it, I don’t fritter money on data plans for smartphones. I carry a pay-as-you-go cell for emergencies. I’m surrounded by people with smartphones, so why do I need one?

“Excuse me.” I smiled winsomely. “Before my accident, I worked for the FBI.”

This is a useful fact: complete strangers are as gullible as eight year-olds. Even though we sat in a place heavily trafficked by the brain-damaged, neither looked skeptical.

“My supervisor sent me a message about a young boy who went missing 17 months ago. I wonder if one of you could Google some information for me?”

Brunette had her Samsung out first--only because Gorgeous had a small seizure. His iPhone was ready a few seconds later.

I asked both to do a search on Jackson Galon. When Brunette reported over 12000 hits, I felt both relief and gloom. I’d counted on him being a figment of my fractured mind.

At my request, she scanned the first three sites and Gorgeous took sites four through seven. She reported that six-year-old Jackson Galon did indeed go missing on the day of my accident. He disappeared from daycare, and it was thought, though it couldn’t be reliably confirmed, that a man had abducted him. His mother and her boyfriend made appeals on the news, and the three of us watched footage on YouTube that I found heartrending. Although the mother seemed blurry as if on tranquilizers, the boyfriend was convincingly stricken as he pleaded for the kid’s safe return.

Brunette found a Facebook page with pictures of Jackson, notes from well-wishers, and progress reports of the search. The last entry was dated four months ago. A quick scan of the site showed that the mother, boyfriend, a babysitter, the boy’s paternal grandparents, a gardener, and eight registered pedophiles in a thirty-six mile radius had all been questioned and cleared.

Gorgeous found an article in the Google search published on the one-year anniversary of the child’s disappearance. Same day as the party my Aunt Ivy threw for me. I’d spent the year undergoing eleven surgeries, learning how to walk again, enduring a monstrous number of crushing headaches, trying and failing to distinguish between true and false memories, between present delusions and reality, and never learning what had happened. Aunt Ivy and the doctors knew more than I did, but my psychiatrist insisted on no one telling me, wanting me to remember on my own. I still knew nothing of the 27 hours before the accident and the 31 days after the accident. I wasn’t entirely sure there was an accident—the same injuries could have been sustained by falling from a building, being caught in a rockslide, or beaten. Aunt Ivy never explained what had happened to my car but took care of negotiating with the insurance company for a replacement as she’d taken care of me and everything else associated with that time.

My psychiatrist suggested calling the incident “an accident” till my memory returned and terminated any discussion where I tried to con her into telling me what had happened. Recently I’d decided to find a new therapist if I still couldn’t remember by the second anniversary, one who would reveal every detail no matter how grisly. I’d only been procrastinating because I wasn’t sure I wanted to know.

Gorgeous read the anniversary interview, and I couldn’t tell if Jackson’s mother still used meds to deal with her loss. The boyfriend, now her husband, was quoted more often than she. He talked about the quiet celebration of the boy’s birthday earlier that month, their no-frills wedding, and crying through the Christmas holidays. Almost as an afterthought, he revealed that she was expecting Jackson’s half-sister in three months. The article quoted the mother, “I know Jax is still alive. Everyday I tell myself that this is the day he will be brought home.”

She called him Jax. That made him more real than all the photos.

At this point, the tiger scratches started to itch. I remembered seeing the scars in the shower this morning, but they hadn’t itched, burned, or even hurt. Hoping the other two wouldn’t notice, I rubbed my thigh. The ridges of the scar through my trousers felt more elevated today.

Gorgeous’s melodious reading did strange things to my spine. The reporter also interviewed other family members and the detective in charge of the investigation. Detective Kohl spent the interview avoiding questions about prime suspects and speculation about whether the boy was alive or dead. She emphasized that the case was still open and encouraged anyone with information about Jackson’s whereabouts to immediately contact the police.

I’d somehow missed this fact in Brunette’s reports, but the interview with the paternal grandparents contained the first mention that Jackson’s father died in a train explosion before his son started school. After their son’s death, the grandparents petitioned the court for custody, claiming the mother was too overwhelmed to raise her son alone. They lost the case. The interview was devoid of explanations or details of how involved they’d been in Jackson’s life.

I was disappointed that the babysitter hadn’t been interviewed, since she interested me the most. She’d been the last to see Jackson. Fortunately, the reporter had been thorough. I wrote down the babysitter’s address as Gorgeous read it off his iPhone.

After asking them to email me the links, I thanked both in the name of the FBI. I’ve never regretted shanghaiing strangers for data mining. People yearn to impart knowledge. I’ve sown happiness in unlikely places, dozens of times.

Sitting in the examination room not much later, I considered everything I’d uncovered. The internet search had intrigued me, and I had nothing planned for the near future. Who called a forty-something, brain-damaged person?

My teacher’s instinct to save kids hadn’t entirely died. Although Video Me with dead Aunt Hillary’s face said that I’d little time to find the boy, I shouldn’t start anything without today’s medical exams. Living with uncertain memories meant questioning everything like: (1) the fortunetelling session last night may not have happened; (2) if it had happened, I could still have made up the name Jackson Galon and everything I’d discovered about him in the waiting room including Brunette and Gorgeous; and (3) if Jackson did exist and disappeared 17 months ago, then I was probably the last person who should be trying to find him.

I had time to see the babysitter before the MRI. While sitting in the exam room in my paper gown, I made two phone calls. One to an ex-student of questionable ethics and notable criminal skills. I would undoubtedly be dabbling in some grey legal areas.

No problem. I’ve done worse.

CHAPTER THREE

At the site of Jackson’s abduction

Belinda Agra still lived in her downtown City of Orange Craftsman-style bungalow. Since Jackson’s abduction happened on her watch, she’d lost her license for after-school daycare. The taxi dropped me off at a neighboring house at 10:15, and I waited beneath a shady tree for my temporary partner and reality checker. From my vantage point, I could read the sign by the door. “Agra’s Doggy Daycare. Reasonable Rates.”

A few minutes after 10:30, a Mustang convertible painted grabber blue roared up and parked behind me. A disgruntled Devlin met me at the sidewalk. “What gives, Ms Graff? V

ice-Principal Bettaker told me to get over here or Coach would bench me for tomorrow night’s game.”

I took a moment to savor using an ex-boyfriend’s power over students for my own gain, before scoffing, “Get over it. He’s giving you community service credit of which I hear you are in such deficit, you may not graduate next year.”

On his face, irritation warred with admiration of my tactical advantage. Even brain-damaged ex-teachers will trump any student any day of the week. In gracious defeat, he growled, “Whatever. What do I gotta do?”

“Back me. Belinda Agra may have been instrumental in the disappearance of Jackson Galon. I plan to question her.”

A smile split his face. “The kid you talked about in your trance? Frigging awesome. Let’s do it.”

As I rang the bungalow’s doorbell amid a cacophony of barking dogs, I reflected that I couldn’t entirely prove that Devlin wasn’t a figment of my imagination. He seemed real, but so did schizophrenic delusions seem to Nobel Laureate John Nash. Still I found his towering presence, real or imaginary, comforting.

The door opened, and a plump woman of East-Indian ethnicity smiled pleasantly. “May I help you?”

Deciding to go with my instincts and my extensive fortune telling experience, I said, “I am a Vedic soothsayer, Mrs. Agra, with good news. I’ve had a vision. Karma smiles on you.”

Her pleasant demeanor vanished. “Shame on you for preying on the ignorant. I’m a Christian woman, lady. I don’t believe in Karma, and you with your blue eyes are no Vedic.” She started to slam the door, but Devlin blocked the movement with a meaty hand. Fear flashed in her eyes.

He must have seen it too, because he said reassuringly, “Sorry, ma’am. Since her accident, my teacher’s gotten weird. As part of a community service project, we’re collecting eyewitness accounts of local crimes.”

Her fear shifted to resigned distrust. “Is this about Jackson Galon’s disappearance?”

I faded into a shadow as Devlin’s disarming presence worked its magic. “Yes, ma’am,” he said.

She hesitated. “I was never charged with anything.”

Time for me to re-emerge. “We’re interviewing only those touched by tragedy, Mrs. Agra. A few minutes of your time would be much appreciated.”

Ignoring me, she asked Devlin, “Does your teacher do anything else strange?”

He winked roguishly. “Strange, yes, but never dangerous. Your story sure would help the program.”

I held my breath as she hesitated and then widened the door. “Thirty minutes. Then I must take Gordo and Rapscallion for a walk.”

Although Devlin held his own in conning Mrs. Agra, I had more years of spinning tales than he. After she poured three glasses of lemonade and set a plate of windmill cookies on the coffee table, I said: “The city has a grant to collect anecdotal data on urban crime during the previous twenty-five years. The city council decided to use high school students escorted by a faculty member to gather the data.” I opened a notebook and clicked a pen. “Do you mind if we record this?”

Before she could respond, Devlin pulled out his iPhone, set it to record, and laid it on the coffee table. She bit her lip. “I suppose …”

“Excellent.” I said to the iPhone, “We’re in the home of Mrs. Belinda Agra. On 04 April, 2012, six-year-old Jackson Galon disappeared from the residence and was never seen again.” I nudged the phone closer to her. “Please tell us the events surrounding the abduction, Mrs. Agra.”

As she twined her fingers nervously, I sipped my lemonade—a little sweeter than I liked it—and flicked a look at Devlin steadily making his way through the cookies.

She cleared her throat. “His mother, Tracy Locksley, dropped Jackson off a few minutes before eight that morning. She worked at an antique store just off the traffic circle. I took the kids to school just before nine and picked them up at two. I cared for six children then, four of them school-aged.” She paused and something like regret crossed her face.

“Before I set them to doing their homework, they had a snack and playtime in the backyard. The back door was open so I could hear them. I was feeding the baby at about 3:00 when the doorbell rang.”

Again she paused, and I had time to study her. Obviously this was a story she’d had to repeat often. Then undoubtedly reviewed over and over in the days that followed. Her arm curled against her waist as if remembering the weight of the infant.

“It was a neighbor lady at the door, said she lived in the green bungalow on the corner, and asked if we’d seen her pet rabbit. She had a flyer she’d been giving to the neighbors. I told her that I hadn’t seen any rabbit like hers when Lydia Patel started wailing in the backyard. It didn’t take but a moment to get to the kitchen door, the neighbor lady following me. Little Lydia told us that a man had come through the side gate and taken Jackson.”

Her lips trembled. “I ran down the side yard while the neighbor lady called the police. The side gate, which I usually kept locked, was open. I looked both ways and didn’t see anything, not even a car. The Circle of Orange is nearby and lots of traffic there, but no cars and no people heading in that direction.

“The neighbor lady told me to stay with the other children while she hurried down the street. She was gone about fifteen minutes. When she returned, she said she hadn’t seen any man or little boy. At first she offered to wait till the police came, but then she remembered she had a doctor’s appointment. I told her to go.”

Mrs. Agra took several swallows of her lemonade. Except for a couple of glances at the cookie plate and intermittent fascination with my shoes when she paused to gather her thoughts, her attention remained fixed on Devlin’s iPhone. “I must have waited for an hour for the police to show. When Lydia’s mother arrived, I told her what happened. She called the police, and they arrived less than ten minutes later. They told me they’d never received the first call. When they checked the green bungalow at the corner, an elderly woman answered and said no one of the description of the woman who’d been at my door lived there. She knew no one on the street who had a pet rabbit either.”

“What did the fake neighbor lady look like?” Devlin asked as I scribbled furiously.

“A white woman about the height of your teacher, but older and plump. She wore sunglasses, a long taupe raincoat, and a flowered silk scarf over her head.”

She made a good witness. Her mouth twisted with mortification for not realizing the woman had been an accomplice to the kidnapping.

“Was Lydia able to give a description of the man who’d taken Jackson?” I asked.

She twined her fingers again. “Lydia was only four. A smart child but fanciful as they can be at that age. She said that Captain Hook had taken the boy.”

Devlin stopped in mid-chew. “From Star Trek?”

“Peter Pan,” I said. “Pirate. Wore a hook after losing his hand to a crocodile.”

He swallowed wrong and choked. Ignoring him, I asked: “Didn’t Jackson raise a ruckus?”

“That was the strange thing. I never heard a peep from the boy, just Lydia screaming. It made the police think the man must have been someone Jackson knew, but the poor child had few men in his life. His father was dead, his step-father at work with a half-dozen witnesses when the abduction happened, and his grandfather, who could never be mistaken for a pirate, was in Laguna Beach. Since the custody case, Jackson’s mother stayed close to home. I understand they didn’t have many friends.”

“Do you have a husband, Mrs. Agra?” I tried to keep the question casual, not load any meaning in the words. Her face darkened.

“My husband travels for his business,” she said icily. “He was in India all of April 2012. And for your information, he also does not look like a pirate.”

She rose, and Devlin hastily downed the last windmill cookie.

“I must walk the dogs now. I hope you have enough for your study.” She wobbled slightly, as if kidnapping memories sapped her.

“One more question,” I asked quickly. Devlin

held his iPhone in her general direction.

“The side gate, you said, was usually locked?”

She nodded wearily, moving towards the door. “The gardener had done the lawns earlier, when the older children were at school. I’d arranged for him to plant trees in the side yard, but he’d run short of time and asked if he could return later. I left the side yard gate unlocked for him. It was never unlocked otherwise. Never.”

Swinging the door open, she spoke with vehemence as if railing against fate or coincidence or chance. Aunt Hillary believed in such things, but I did not. As Devlin and I left the small bungalow, I felt sure someone had orchestrated the abduction from the lost rabbit to the unlocked garden gate.

An unexpected interview nearby

Before leaving for football practice, Devlin emailed me the interview’s audio file so I could review it later that day. He waved jauntily as he roared off in his Mustang convertible. He’d made an able assistant, and I planned to line up others. Witnesses and anything recorded would be proof of reality over hallucinations.

I studied the narrow street, my gaze resting momentarily on the side gate. If anyone had been at a house directly across the street that day, they would have seen someone dragging or carrying a child from the yard.

Children today were trained to be wary of strangers. At six, Jackson would have fought a stranger, forcing the kidnapper to gag him, or resort to drugs to keep him quiet.

I checked my watch, and decided I had time before the taxi returned to query a couple of neighbors. I’d asked my brother Charlie to get me the police file (I figured the one online was missing information), but it couldn’t hurt to ask a couple of questions of my own.

No one answered at the house directly across the street, but a young girl, about ten-years-old, sat morosely on the porch of the house next to it. “Is your mom home?” I asked.

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2)

Indelible Beats: An Abishag's Second Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 2) Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1)

Sinking Ships: An Abishag's First Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries Book 1) Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries)

Riddle in Bones: An Abishag’s Third Mystery (The Abishag Mysteries) Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2)

Egrets, I've Had a Few (Deluded Detective Book 2) An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4)

An Eggshell Present: An Abishag’s Fourth Mystery (Abishag Mysteries Book 4) Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1)

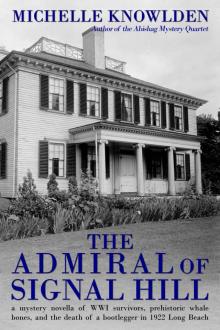

Jack Fell Down: Deluded Detective Book One (Deluded Detective Series 1) The Admiral of Signal Hill

The Admiral of Signal Hill